Meditation Circle member Robin Wilson is in Moscow, visiting his son and daughter-in-law (she’s a New York Times correspondent posted to Russia). He e-mailed this blogpost to us on Sunday:

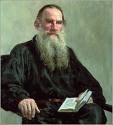

Yesterday, I visited a Tolstoy Museum in Moscow. Tolstoy was the inspiration and name for the first commune I moved to in 1964. Tolstoy became a champion of nonviolence, vegetarianism, simple living, anti-inheritance, free schools, and anti-authoritarian government through his writing and experiments. Also, as the piece from Wikipedia below points out he was influenced by Buddhist thought. In a nice example of international “what goes around comes around,” Henry David Thoreau influenced Tolstoy, who influenced Gandhi who influenced Martin Luther King. ~ from Robin Wilson

The years 1856–61 were passed between Petersburg, Moscow, Yasnaya, and foreign countries. In 1857 (and again in 1860-61) he traveled abroad and returned disillusioned by the selfishness and materialism of European bourgeois civilization, a feeling expressed in his short story “Lucerne” and more circuitously in “Three Deaths.” As he drifted towards a more oriental worldview with Buddhist overtones, Tolstoy learned to feel himself in other living creatures. He started to write “Kholstomer,” which contains a passage of interior monologue by a horse. Many of his intimate thoughts were repeated by a protagonist of “The Cossacks,” who reflects, falling on the ground while hunting in a forest:

The years 1856–61 were passed between Petersburg, Moscow, Yasnaya, and foreign countries. In 1857 (and again in 1860-61) he traveled abroad and returned disillusioned by the selfishness and materialism of European bourgeois civilization, a feeling expressed in his short story “Lucerne” and more circuitously in “Three Deaths.” As he drifted towards a more oriental worldview with Buddhist overtones, Tolstoy learned to feel himself in other living creatures. He started to write “Kholstomer,” which contains a passage of interior monologue by a horse. Many of his intimate thoughts were repeated by a protagonist of “The Cossacks,” who reflects, falling on the ground while hunting in a forest:

‘Here am I, Dmitri Olenin, a being quite distinct from every other being, now lying all alone Heaven only knows where – where a stag used to live – an old stag, a beautiful stag who perhaps had never seen a man, and in a place where no human being has ever sat or thought these thoughts. Here I sit, and around me stand old and young trees, one of them festooned with wild grape vines, and pheasants are fluttering, driving one another about and perhaps scenting their murdered brothers.’ He felt his pheasants, examined them, and wiped the warm blood off his hand onto his coat. ‘Perhaps the jackals scent them and with dissatisfied faces go off in another direction: above me, flying in among the leaves which to them seem enormous islands, mosquitoes hang in the air and buzz: one, two, three, four, a hundred, a thousand, a million mosquitoes, and all of them buzz something or other and each one of them is separate from all else and is just such a separate Dmitri Olenin as I am myself.’ He vividly imagined what the mosquitoes buzzed: ‘This way, this way, lads! Here’s some one we can eat!’ They buzzed and stuck to him. And it was clear to him that he was not a Russian nobleman, a member of Moscow society, the friend and relation of so-and-so and so-and-so, but just such a mosquito, or pheasant, or deer, as those that were now living all around him. ‘Just as they, just as Uncle Eroshka, I shall live awhile and die, and as he says truly: “grass will grow and nothing more”.’