A friend and I who attended Miami University together in the late ’70s had hoped to see H.H. the Dalai Lama upon his visit to our alma mater later this month in Oxford, Ohio. Alas, tickets went fast and furiously and mostly to Miami students. I consoled myself with having had the blessing of seeing the Dalai Lama speak on two prior occasions, once in a dialogue in Belfast with a Christian monk and once in 1998. From the archives, I offer this depiction of a day-long Lojong training and talk given by His Holiness at American University in D.C., in November 1998. The article was originally written for Hundred Mountain, a Buddhist online journal I used to publish on the Web.

WASHINGTON, D.C. | November, 1998

by douglas imbrogno

DOWN ON THE CORNER OF 12th AND K STREETS, it sounds like a riot. I push open the rubbery Days Inn curtains and look down six floors to the corner of 12th and K streets. It is 3 a.m. The nation’s capital–or at least this neck of the woods–has not gone gently into the night. Honking cars cram the intersection on this cool November Friday night. A knot of young black guys laughs, shouting at the top of their lungs and then one starts swinging. He is tackled to the ground, scrambles up and flees into the darkness. Women in short skirts sidle up to car windows, lean in.

Can’t hotel staff put the kabosh on this after hours street theater? Don’t people know His Holiness the Dalai Lama is in town? Where are the cops? Those of us who drove hundreds of miles to drink up the fellow who has become a sort of alternative pope for some Westerners need our rest. We have a full day ahead. Six hours of instruction in Lojong mind training. Shut up, world! (Is that an un-Buddhist sentiment?) The revelry continues past 4 a.m., when it finally dries up and blows out. The streets empty. Tendrils of a rosy dawn soon creep into the capital sky.

H.H. the Dalai Lama was the hot ticket in town, and in fact, all along the Eastern Seaboard. It was an odd thing. The Dalai Lama had for years barnstormed across America. Yet this past fall, his appearances in Washington, in Pittsburgh and elsewhere merited widespread mention and coverage in the popular media. Slow news week? Or was the Tibetan spiritual leader still just way cool?

It was no small potatoes to be in the same room with him. Just to sit in the bleachers in the cheapest seats in the gym at American University—the site of the Lojong training—cost $35. For $85, you got a fold-down seat. And $115 got you down on the gym floor within eye-ball-to-eyeball distance of him. That would be an auspicious thing, I was told. Just to hear him, just to be in the same room with such a highly realized teacher, earned merit for you in the karmic sense of things, said the contractor who had invited me to come with him for the event. A gymnasium, would count, too.

I’d never seen His Holiness in person. My contractor friend, Ken Lewis, had seen him numerous times. He never missed the chance for a Dalai Lama road trip when His Holiness was anywhere within striking distance of Ken’s home in Spencer, West Virginia. This time, he’d lined up his wife and son, as well as a Spencer schoolteacher friend, plus myself, a longtime student of Therevadan Buddhism.

We popped for the $85 fold-downs. The schoolteacher took it to the bank so he could sit down on the gym floor. Income from the talk was to be used to support a multi-year project including an event the summer of the year 2,000 on the National Mall in the capital, something called “Tibetan Culture Beyond the Land of Snows.” Ken won over an niggling doubts about the propriety of spending so much money for what amounted to a five-hour lecture: “If I trust anyone with how my money would be spent, it’d be the Dalai Lama.”

A BUDDHIST HAPPENING

We were in good company. The Friday night before the event we ate dinner at an Italian restaurant a few blocks from the White House. At one point in the evening, a man with a great shock of grey-black hair and wearing a tweed jacket with elbow patches crossed the room.

Ken looked up from his forkful of pesto linguine. “That’s Robert Thurman!” he cried.

It helps to know that Ken—whose day job is building houses and U-Store-It buildings—is founder of West Virginia Friends of Tibet, a Buddhist meditator of many years, and an omnivorous reader of Buddhist books and articles, including ones written by Robert A.F. Thurman. Thurman is one of the West’s leading Buddhist commentators and scholars. He is also a significant Western player in the Dalai Lama’s American support group for the cause of Tibetan autonomy in the face of China’s long reign of repression in the exiled spiritual leader’s homeland.

Oh, and Thurman’s daughter is beautiful Hollywood star Uma Thurman.

Ken’s son, Ryan, sitting across the restaurant table, would no doubt report back to friends at his high school that he had seen Uma Thurman’s dad. His father had glimpsed a star of  a different sort. Setting down his fork and wiping his mouth with his napkin, Ken flagged Thurman down as he passed nearby.

a different sort. Setting down his fork and wiping his mouth with his napkin, Ken flagged Thurman down as he passed nearby.

“I just want to shake your hand.” Ken said, gripping Thurman’s in his own.

A smiling Thurman didn’t miss a beat. Perhaps he was used to this sort of thing in the spirited circles he traveled. He graciously greeted everyone at the table, asked us where we were from, wished us well and resumed his interrupted bathroom quest. We moved on to bowls of pistachio-flavored gelato, pleased with the feeling that we were part of a Buddhist happening.

H.H. the Dalai Lama certainly fit the definition. That would be the Buddha’s definition of “The Holy Person,” from chapter 26 in “The Dhammapadda,” the collected verses of the Buddha’s essential teachings:

“One who without resentment endures abuse, beating and punishment, whose power, real might, is patience—such a one do I call a holy person.”

Yet exactly because he was so powerfully, so firmly patient in the face of the untold suffering inflicted upon Tibet by China these last 40 years, the Dalai Lama was a dangerous figure to the Chinese government. It was hard to reckon that such a man could be dangerous—and also be in danger. Yet hadn’t an assassin poured bullets into Mahatma Ghandi’s chest?

MEN IN SUITS

So it was that instead of striding into the university gym that Saturday morn, several thousand of us stood in line in cold rain, sipping lukewarm coffees, waiting to walk through an airport metal detector arranged at the door. We had to have our bags, purses and persons examined, to sift out guns, knives, blowdarts or whatever else a sickened soul would take in to try and take out this man they call His Holiness. Who would do such a thing? Would the Chinese dare it? Or those disaffected followers of a Tibetan diety that the Dalai Lama had frowned upon? Or your garden variety wacko in search of negative karmic grandiosity? Had there been threats? Or was fin-de-siecle America just too crazy?

Men in suits, with short neatly trimmed hair and earholes plugged with receivers, eyed the line. Asked what their shiny-red lapel pin that read “D.S.S.” stood for—Dalai Lama Secret Service?—one of them replied: “Diplomatic Security Service of the State Department.”

The ticketholders formed a multi-ethnic conga line several hundred yards long, snaking uphill along a sidewalk. Five thousand tickets had been sold or given out and a small but significant contingent included Eastern and Western Buddhist monks and nuns. The maroon and orange robes of Tibetan and Therevadan monks mingled with the occasional Zen figure in grey and black. The deep-hued faces of several hundred lay Tibetans adults and children, some dressed in formal Tibetan clothes splashed with color, added to the mix, evidence of the Tibetan diaspora’s deepening roots in America.

There were few black faces—par for the course in the vexsome issue of Buddhist America’s chiefly white, middle and upper middle class makeup.

The security precautions proceeded to bollox things up. The event was to start at 9 a.m. But when that bewitching hour came several thousand people stood outside the building, still awaiting their electronic frisking. Our party had passed the mark by then and was seated in the nippy gym. But the organizers’ miscalculation —5,000 people funneled through the keyhole of a single metal detector—had repercussions. We would lose nearly an hour of our mind training time and not start until 10 a.m. as the crowd continued to trickle in. As a sort of spiritual sop, a half-dozen Tibetan monks mounted the stage and sat cross-legged in a rustle of orange robes. They commenced to chant, filling the gymnasium with the now-familiar bullfroggy, polyphonic, throat singing that itself is supposed to bring spiritual benefit to listeners. We huddled in our coats and sweaters, hoods up who had them, tuned in and gained some merit.

AN OCEANIC STILLNESS

Word was that Richard Gere was somewhere in the place. Not to mention, of course, Uma Thurman’s dad. Gere, Hollywood’s highest profile Buddhist—and a prime financial backer in the West for the Dalai Lama’s Tibetan cause—was keeping a low profile, perhaps so he wouldn’t be mobbed, perhaps to direct attention to the day’s real order of business. I would have liked to have seen him. I respected Gere, a serious and thoughtful Buddhist practitioner, who did not at all deserve the “recreational Buddhist actor” caricature sometimes hung upon him. Thurman was out in the open, though, and his standing in the Buddhist world was evident. He sat in the front row down on the floor, to the right of a small stage decorated with Buddhist imagery and fresh flowers. The Dalai Lama would greet Thurman personally as His Holiness entered the arena.

For it was time for the entrance—and it was a big one. I don’t mean to suggest that it was staged for effect. But it had a powerful resonance. “His Holiness is about to enter the room,” an organizer said into a microphone on stage. “Please take a moment of quiet to prepare yourself for his entrance.”

Outside the walls of churches, mosques, temples and monasteries, one forgets in today’s noisy, rude and fulsome world the stirring power of a few moments of respectful silence. The bustle and buzz of 5,000 people fell almost instantly away into an oceanic and expectant stillness. You could literally hear the rise and fall and rise again of your own breathing. That seemed apt for the entrance of a great monk who dispensed fundamental teachings that stressed breath-centered spiritual practice.

Whether you believed the Dalai Lama to be a highly evolved spiritual figure worthy of such reverence (he calls himself “a simple monk”) or just another celebrity worthy of curiosity, all eyes fixated upon the small beaming figure who hustled into the room swathed in folds of maroon and gold robes.

The dozens of Tibetan monks in attendance prostated themselves three times upon the floor. Many of us in the audience held our two hands templed together in a namaste of greeting and reverence. Ken and other spiritual veterans of Tibetan Buddhism dipped their heads low—lower than the teacher’s—in extra-special reverence. A pony-tailed and bespectacled college student nearby bowed, then resumed running his fingers along a mala of brown prayer beads thick as peas, lips silently mouthing blessings, as he had done all morning long.

The Dalai Lama’s famous cheerfulness was everywhere in evidence. A “ripple of mirth” washed outward from him across the big room, to borrow a phrase someone once used to describe another Tibetan’s monk’s demeanor. Slightly hunched over, His Holiness beamed right and left at people, greeting as many as he could. There was a whole lot of merit going on. Especially for the Tibetans on hand, such an encounter was great good fortune, an auspicious blessing. Back home, Tibetans who even possess the Dalai Lama’s photograph have been imprisoned and tortured by Chinese troops, vigilant to quash his support.

He mounted the stage, offered a namaste to the audience in several directions, removed his shoes and ascended the steps of a five-foot-high dais.Beside the dais stood a chair and table with a microphone for his longtime Tibetan translator. Standing atop the dais on a soft cushion, the Dalai Lama elicited the first belly-laugh of the day, bouncing with Charlie Chaplin-esque exaggeration three times. ‘Ah!” he said, grinning. The dais was indeed sturdy enough for a simple monk.

MY SACRED FRIEND?

The Tibetans teach sometimes via long, complex talks and analysis whose sum and substance are not easily summed up in a few quotes. On a superficial level, you could say that His Holiness the Dalai Lama spoke—through stilted English and translated Tibetan—to the power of radically positive thinking. After all, verse six of the eight Lojong verses for training the mind is this:

“When someone whom I have helped

or in whom I have placed great hope

harms me with great injustice,

may I see that one as a sacred friend.”

Yikes. Your enemies are your beloved teachers, too, in other words.

An essential skill on the way to spiritual awakening is countering harmful, hateful and grasping mental states of mind, through constant mental discipline and insight into how we have helped to create our own suffering states, he said. “It is the undisciplined state of mind that is the origin of suffering.”

“If you let negative states arise without restraint, you are in essence giving them free reign. As they occur—instantly and immediately if you have the mindfulness—you don’t give them the opportunity to develop into a full-blown negative emotion or thought.”

And if they do, you work moment-to-moment to counter such emotional and mental defilements with “antidotes” of compassion, insight and fellow feeling for yourself and others. Generating humility is an antidote to arrogance and pride, for example. This includes the spiritual pride that tempts even him to wonder if people are enjoying his teachings and how well he is doing, he said. When he thinks he has it all figured out, said a smiling Dalai Lama, he administers a little anti-arrogance antidote. “When I have a little tingling sensation of pride, I think of computers.”

This Lojong training—Buddhism’s all-pervading compassion mixed with a constantly alive and vigilant mindfulness—wasn’t for wimps and people looking for an easy out. As another Lojong verse put it:

“May I examine my mind in all actions

and as soon as a negative state occurs,

since it endangers myself and others,

may I firmly face and avert it.”

The difficult business of working with difficult emotions—and difficult people like the co-worker who drives you crazy and who you’d rather throttle than love, or the street person you want to bazooka down on 12th and K who’s keeping you up—well, it was your life’s work to keep up with these mental states.

“When I see beings of a negative disposition

or those oppressed by negativity or pain,

may I, as if finding a treasure,

consider them precious, for they are rarely met.”

No throttling allowed—and certainly no bazookas.

On a daily basis it is essential to take better care of the mind by generating more wholesome thoughts and by taking to task unwholesome ones, said His Holiness. “In talking about Buddhist training of the mind, valid thoughts are developed,enhanced and perfected. Invalid thoughts and emotions are undermined and eliminated eventually.”

And don’t expect some secret teaching to get you out of your ultimately self-dug hole of suffering. “There is no magic key. Therefore, we need more determination. And more patience.”

JUST SIT HERE

By day’s end, he had lectured farther and deeper afield. He spoke of the interrelatedness of all that we call reality, that puny, inadequate and constantly misleading notion. And he took on one of the subtlest, most difficult and far-reaching of Buddhist teachings—reality’s ultimate emptiness of any actual, absolute existence and the liberation that can result from this awareness.

These points in the teaching demanded close attention. And the Dalai Lama’s often professorial and analytical dissection at length of the minutie of the spiritual path—”Self and person should be understood as a designation dependent on mind and body…”—led more than a few of us to waver in our attention at times. Leastwise I didn’t drift off to la-la-land like the shaved-headed fellow slumped over on his girlfriend’s shoulder across the aisle. At those moments, I’d rouse up some extra energy—energy-rousing for wholesome purposes being expressly encouraged by the Buddha—and the rewards were always good. “Not a charismatic speaker,” Ryan remarked at one point. But this this was a teaching lecture, after all. If you stayed the course most of the time, big, filling insights stuck to your ribs. Nourishment for the days and weeks ahead when the celebrity rush of seeing the Dalai Lama had dissipated and you were left with—what? Something to work with.

Yes, and there were a few laughs along the way, too, for which he is also famous.

One of the questions from the audience at day’s end was: “Do you forsee any catastrophic world events at the millenium, and how should we prepare for them.” The Dalai Lama grinned as the translator read out the question. He scratched his bald head with one crooked arm then guffawed, as the audience burst into laughter along with him.

“I dunno!” he exclaimed. “If there is some major disaster in one place, so run to another place.”

And if the whole world goes up in smoke?

Smiling, he gestured to his cushions.

“Just sit here.”

EPILOGUE

This Buddhist business of taking total responsibility for not only your overt actions in the world, but your moment-to-moment mental states—the fertilizing and nurturing of positive ones, the culling and replanting of poisonous ones— is an alarmingly big job.

My mind rebels, it’s cozy with its bad habits. It has had it way for decades. Those grooves of unwholesome habits and behavior—killing rage, zombie-eyed lust, Olympian self-absorption,to name just a few—run deep. Hard to get my wagon wheels out of them.

I drive the 12 hours home on slick roads through the Appalachian mountains, feeling emboldened, charged up with spiritual resolve, heartened simply by recalling being in the same room as the Dalai Lama and seeing that cheery face. Yet also I feel fragile. Off in the darkness beside the interstate in the middle of West Virginia, a huge neon sign invites all comers to a gargantuan strip joint for truckers. My longtime companion the zombie speaks up—wouldn’t a little bare anonymous flesh on parade taste good about now?

Oh boy, I’ve got my work cut out for me.

Can’t say I’ve really worked the eight steps of the Lojong training per se, although they resemble lines from my Therevadan Buddhist practice that I do recite now and again. It’s the same thing. Rouse up that energy. Keep tabs on that mind. Generate wholesome feeling, notice the staying power of the unwholesome. Work out your own salvation, as the Buddha famously reminded his followers in perhaps his final and most succint teaching, with diligence.

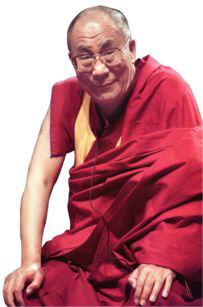

A picture of His Holiness the Dalai Lama now hangs on the bulletin board beside my computer at work (the same one that graces this article) and in a niche of my home meditation space. Not for any worshipful reasons—he’s a simple monk after all, on a not-so-simple mission. Just like all of us.

Or maybe it’s all far more simple than we, in our hysterical, distracted, self-sabotaging daily lives, are able to see?

All I know, is this—I need all the help I can muster.

LOJONG: Eight verses for Training the Mind. Offered by H.H. the Dalai Lama at American University

By thinking of all sentient beings

as even better than the wish-granting gem

for accomplishing the highest aim

may I always consider them precious.

Wherever I go, with whomever I go

may I see myself as less than all others,

and from the depth of my heart

may I consider them supremely precious.

May I examine my mind in all actions

and as soon as a negative state occurs,

since it endangers myself and others,

may I firmly face and avert it.

When I see beings of a negative disposition

or those oppressed by negativity or pain,

may I, as if finding a treasure,

consider them precious, for they are rarely met.

Whenever others, due to their jealousy,

revile and treat me in other unjust ways,

may I accept this defeat myself,

and offer the victory to others.

When someone whom I have helped

or in whom I have placed great hope

harms me with great injustice,

may I see that one as a sacred friend.

In short, may I offer both directly and indirectly

all joy and benefit to all beings, my mothers,

and may I myself secretly take on all of their hurt and suffering.

May they not be defiled by the concepts

of the eight mundane concerns,

and aware that all things are illusory,

may they, ungrasping, be free

from bondage.